Archival Processing & Collaging Photographs with Joseph Rovegno

- Name, where are you from, what format you like using, what are you currently working on if you are?

I am Joseph Rovegno. I’m from New York, and that’s where I’m based. I use film in all formats, always shooting 35mm with small cameras, but I also shoot in formats up to 4x5.

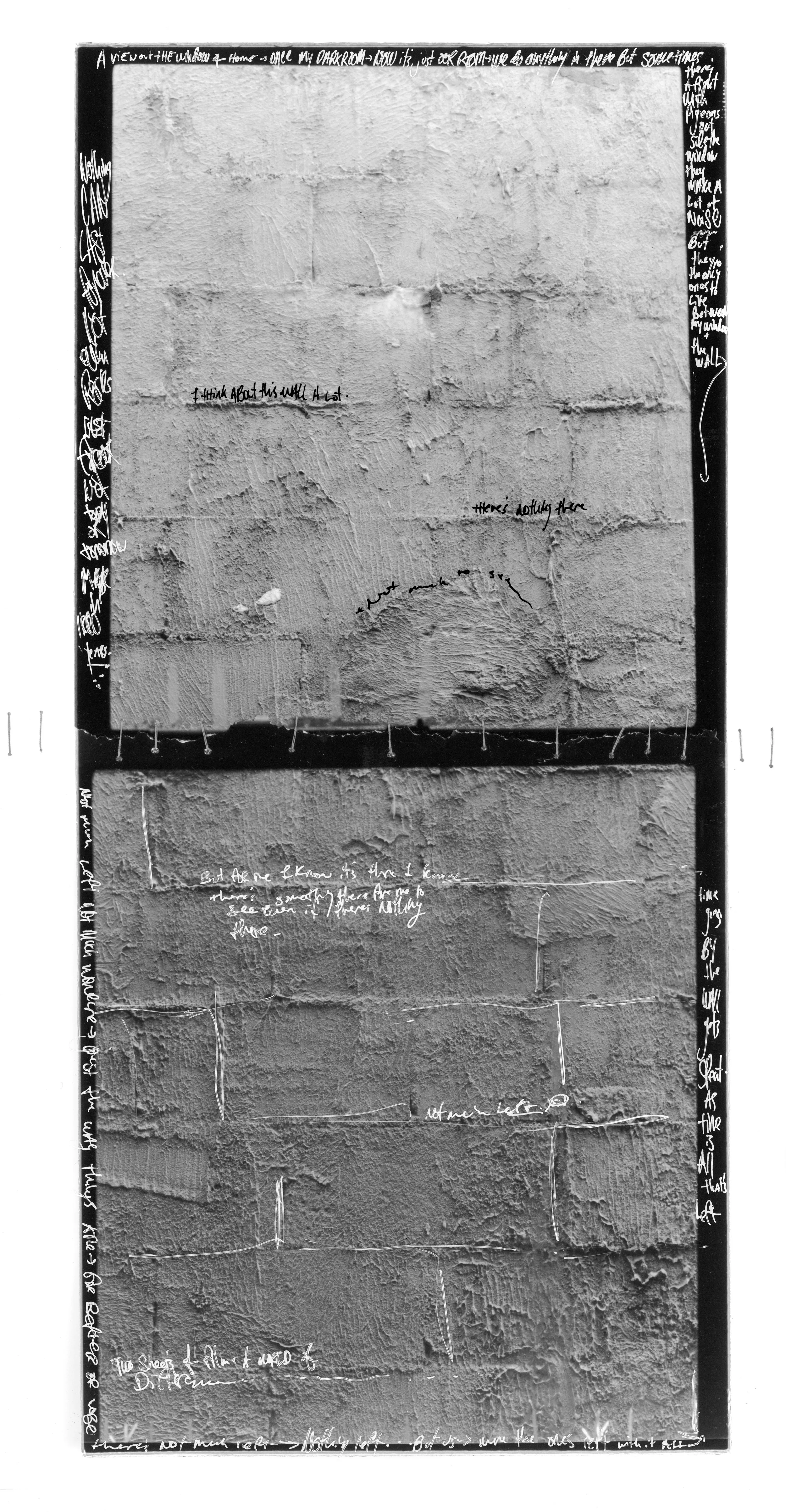

When I develop my film, I work in the black and white darkroom, making contact sheets, then small prints, then sometimes larger tiled prints. Sometimes I experiment with plantium printing, and I’ve begun using image transfers to let my pictures live on non-traditional surfaces, like cement and stone. Eventually, my work usually ends up in a handmade book.

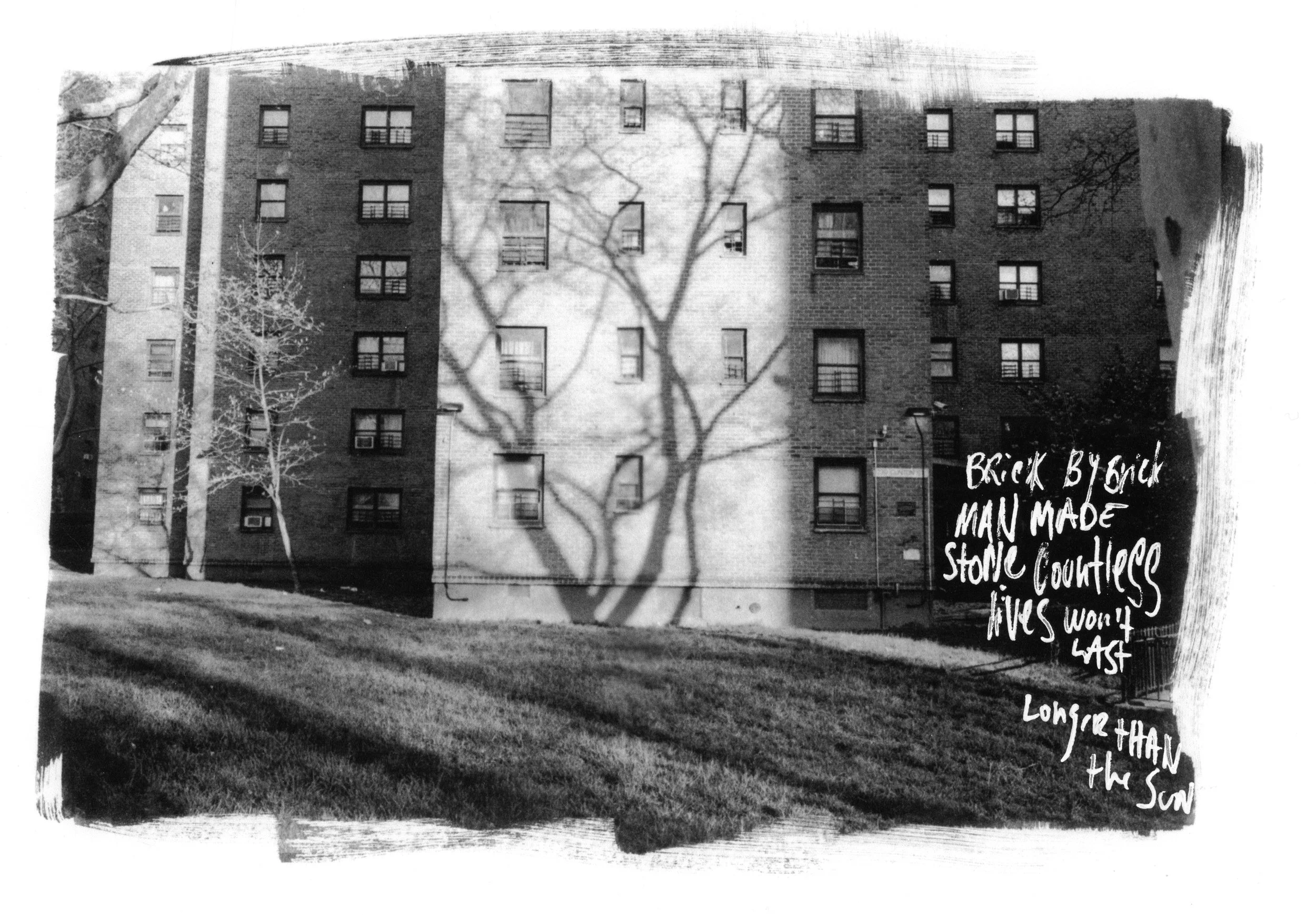

I’m currently working on pictures related to rocks. I’ve acquired a deep fascination with rocks. The idea of a rock. How it lasts forever, but also really doesn’t. On a long enough timeline, a rock and a person expire the same way. Same with a picture. None of these things last forever.

- When was the first time you met photography? How did you feel when you met it?

The first time I really got to know photography well was during a psychosis, when I was taking photos compulsively in an erratic way. This laid the groundwork for the way I try to see now.

- Tell us about current projects you have been working on (could be any, or just work you have been doing in general). Is this story inspired out of personal reasons, or others? What are you most excited about in these projects?

Continuing with the rocks. It’s called the Memory of a Rock. It is exciting because I feel it’s infinite. I can spend a lifetime following rocks and wouldn’t even find a fraction of a percent of them. Of course, the pictures aren’t about rocks. Sometimes they are. But more of the idea of a rock.

It started when I began diving deep into archival processing of fiber prints. Wash time, toning, storage, acid-free material. Humidity. All of the preservation and best practices for making a fine print. I thought even when all these steps are taken, it’ll last 100-200 years if you’re lucky. For platinum/palladium, a more stable metal, 1000 years. I thought about things you’d see in the MET. Not photographs, but artifacts —things carved into stone. I sent a note to an artist named John Divola. He came up in the 70s & 80s, working within conceptual art. He witnessed land art (Earthworks), where artists were using the Earth as a part of their medium. I asked if anyone has printed photos on stone, given photography’s fetish with permanence. He replied, telling me to visit any cemetery. That’s when it started, and has morphed to experimenting with stone lithography, engraving into granite, image transfers onto cement, embedding silver gelatin prints into concrete, or just taking photos of rock.

- How did you find your visual literacy? Why are you attracted to certain images more than others?

I was put on to the work of Daido Moriyama when I made a small zine about my friend’s tattoos. This opened my eyes to treating an individual image as less important than a series (or sequence) as a whole. Especially in an abstracted way. Then, before knowing anything about photography history, I found “The Lines of My Hand” by Robert Frank in a used bookstore. To this day, it’s my favorite. I was drawn to it for its mix of image and text—handwriting, mark making and collaging.

- Imagine meeting someone who is picking up a camera for the first time. What do you tell them?

I’d tell them to take pictures of their life, and take a lot of pictures. You are the only one who can tell that story. It’s most unique to you, so it’s the most interesting thing for you to shoot.